As the year winds down, I pause and look back at the stories that kept me company. Reading has always been my favourite way to unwind and escape. It is a quiet pocket of calm in otherwise busy days, and this year, books played that role more than ever.

I began January with a modest goal of 60 books, only to raise it to 75 midway through the year once the momentum kicked in. Not every pick was a win though; there were a few disappointments and some DNFs, largely because I spent too much time chasing curated lists instead of my own reading instincts.

While most of my reading usually happens on a Kindle or via Audible, this year saw a surprising return to physical books. The real highlight, however, was joining a book club that perfectly matched my vibe. I finally found my tribe and a space where conversations about books feel just as rewarding as reading them.

So let’s kick off the reviews with my Fiction reads of the year. I started off strong with Han Kang. Human Acts was my favourite of hers. Orbital took me into outer space in a dream-like hopefulness; Butter was unexpected; and Small Things Like These was a revelation in a tiny package.

The Vegetarian, by Han Kang (Translated by Deborah Smith)

Reading the reviews, I assumed The Vegetarian by Han Kang was just about society’s opposition to a person challenging the norm. But it is so much more, where Han Kang explores repression, autonomy, and trauma.

The book is divided into three parts, each narrated by someone close to the main character, Yeong-hye. She has a dream that makes her turn vegetarian in a culture where it’s practically unheard of. Her own POV is not mentioned, as if it is not important.

Her husband narrates the first part. He is content with his mediocre life, which turns into an upheaval when his wife decides to turn vegetarian. He violently tries to make her see sense, then eventually gives up and leaves.

Yeong-hye’s decision to give up meat—a seemingly simple choice- spirals into a disturbing journey of alienation and self-destruction. Her quiet rebellion against traditional expectations exposes the fragility of her relationships and the oppressive structures that define them. No one tries to understand the root cause of her decision; instead focus on ‘fixing’ her somehow.

Read my full review here: Han Kang Book Review

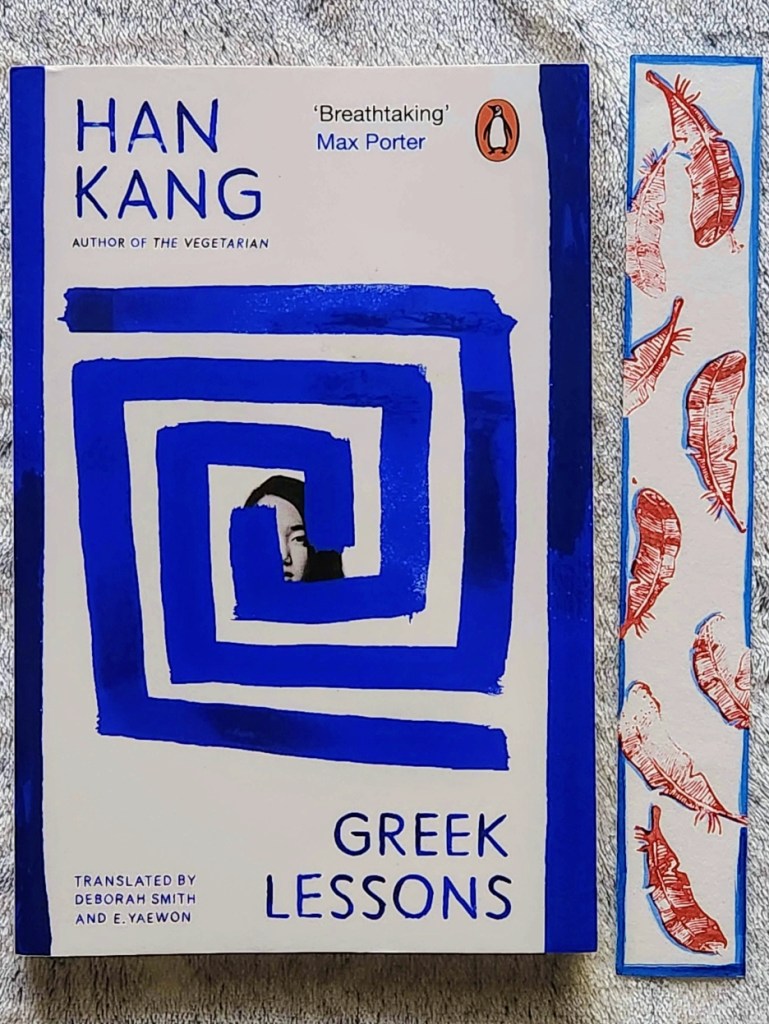

Greek Lessons, by Han Kang (Translated by Deborah Smith and e.yaewon)

In Greek Lessons, Han Kang tells a story about two people navigating loss and loneliness in their own ways, yet somehow finding a fragile connection with each other. The novel gives us two perspectives: a Greek language professor slowly losing his sight and a woman who has lost her voice, both literally and figuratively.

Read my full review here: Han Kang Book Review

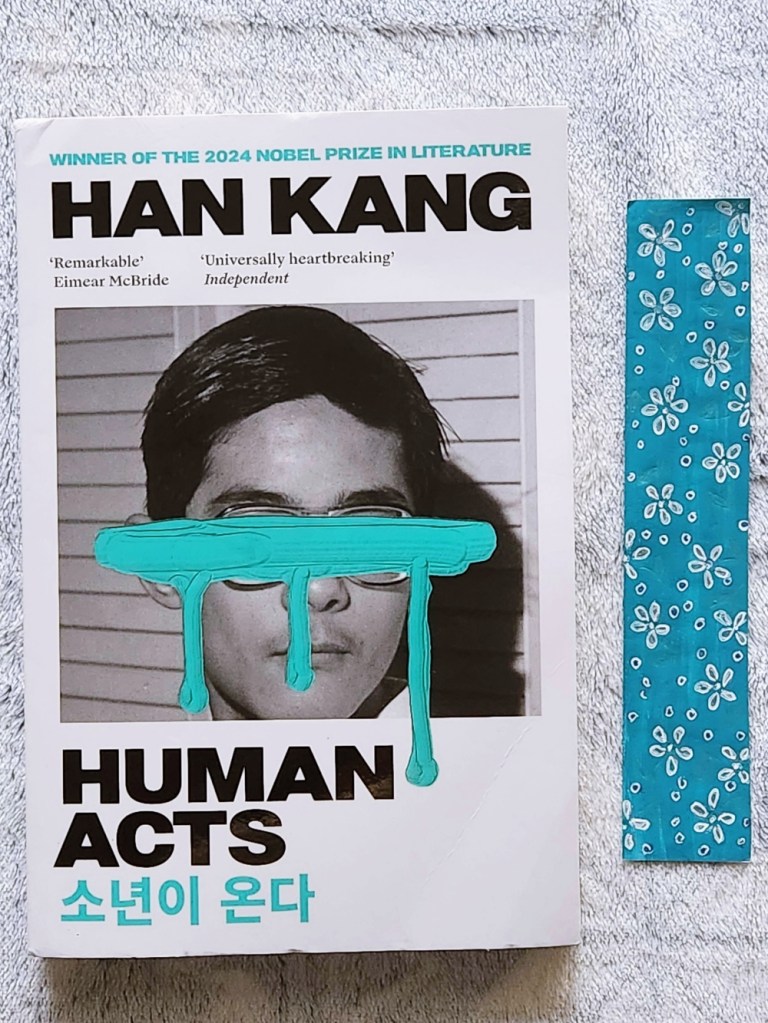

Human Acts, by Han Kang (Translated by Deborah Smith)

There are two ways to read this book. You can feel everything, which is terrifying, or you can read it indifferently, which is also terrifying. Either way, you’ll need a moment to grieve at the end of it.

Partly based on true accounts and partly fiction, Human Acts recounts the stories of various people during the 1980 Gwangju Uprising and the years that followed. Each story is told from the viewpoint of a different person at a different point in time, each grappling with grief, trauma, and the lingering scars of political oppression.

Read my full review here: Han Kang Book Review

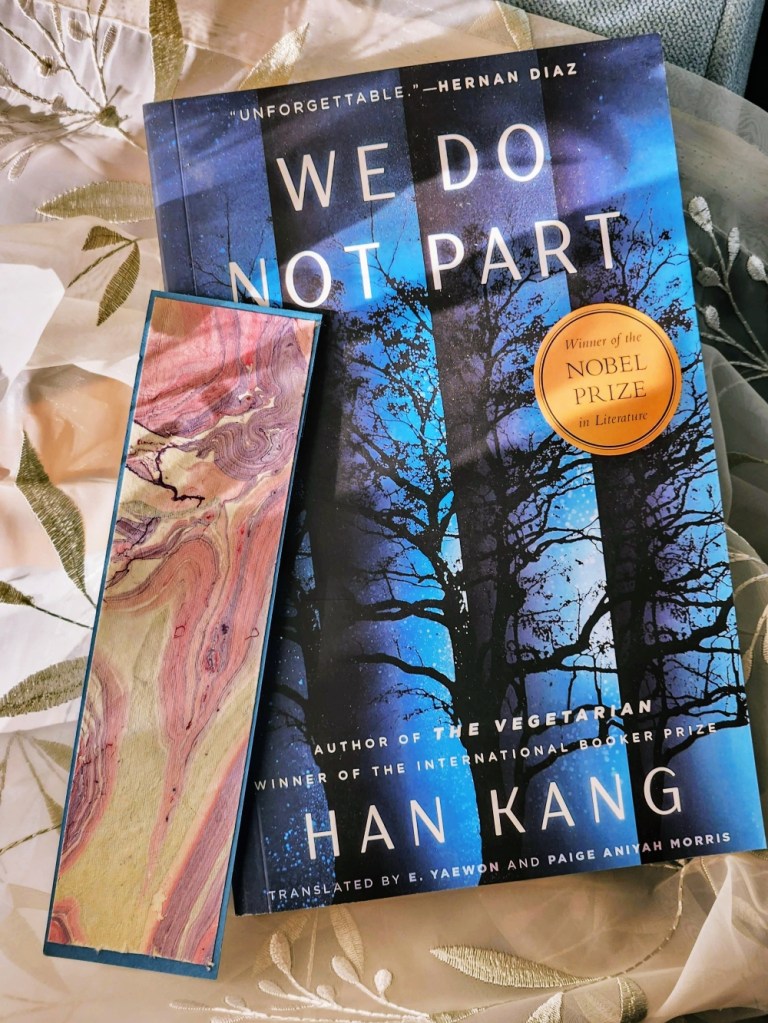

We Do Not Part, by Han Kang (Translated by e.yaewon and P.A. Morris)

In We Do Not Part, Han Kang doesn’t explicitly tell you about the violence that has been committed. She eases you in with a friendship between two women, talks about despair, and then the floodgates open. Inseon has suffered a serious woodworking injury (I would give a trigger warning, but then the whole book would be redacted). She calls a trustworthy friend she hasn’t spoken to in years to go to her secluded home on Jeju Island and save her pet bird. Kyungha makes her way through a snowstorm and is reminded of all that has happened on this tiny island, not too long ago.

This harrowing history is told so poetically that you get caught up in the flow. Even after 50-60 years, the collective trauma lingers somewhere deep, and meaningful human connections are all that keep people living somewhat sane!

Read my full review here: Han Kang Book Review

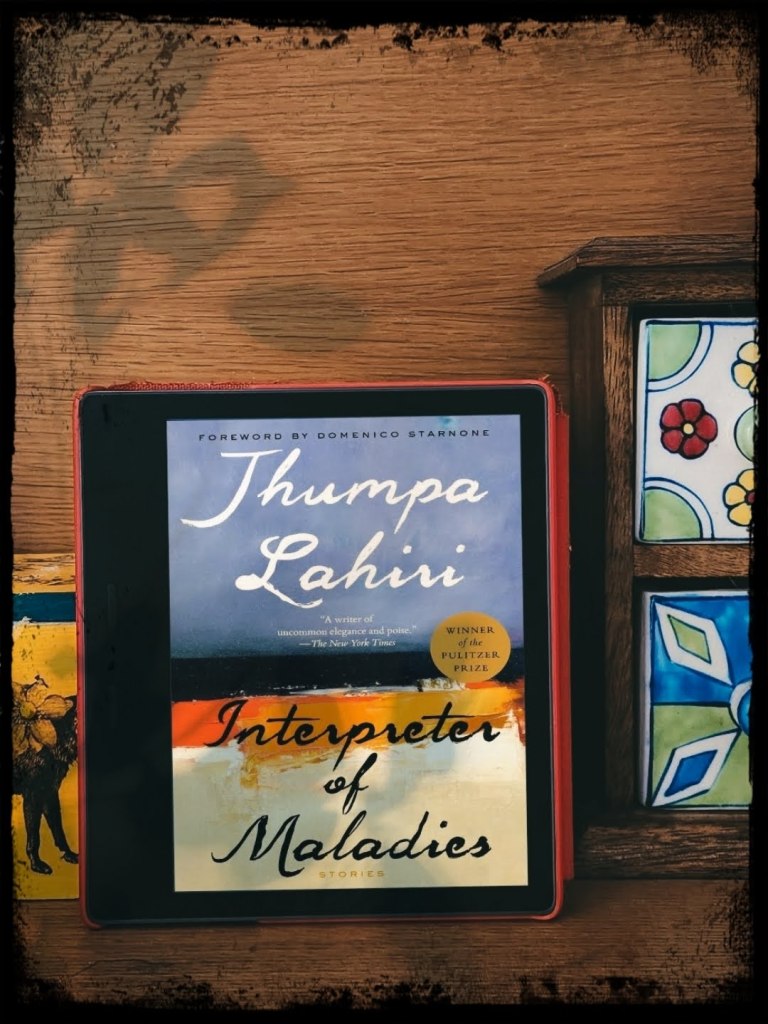

Interpreter of Maladies, by Jhumpa Lahiri

Interpreter of Maladies is one of the best short story collections I have read in a while. Through these stories, she paints a vivid portrait of the immigrant experience and the quiet struggles of identity and belonging.

The writing style is simple but conveys a strong emotional depth. Characters grapple with their identities as immigrants straddling two cultures. It is easy to empathise and sympathise with the characters.

I enjoyed each of the short stories. My favourite has to be The Third and Final Continent, with A Temporary Matter coming a close second. Every story is so well crafted that it is no wonder this debut book won her the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

Read my full review here: Interpreter of Maladies Book Review

The Easy Life in Kamusari, by Shion Miura (Translated by Juliet W. Carpenter)

A nice, easy-going book about a young man who has had to leave his city life to learn forestry in a remote mountain village. Nothing exciting or adventurous happens, and even the storyline doesn’t have any conflict resolution at the end. Like the title says, it’s about the easy life.

I enjoyed reading the book without expectations, and it helped me wind down at night as well. Just reading about the forest and village life descriptions relaxed me. There is some humour, sadness, and lots of myths as Yuki adjusts to his new life.

Read my full review here: Kamusari Forest Series

Kamusari Tales Told at Night, by Shion Miura (Translated by Juliet W. Carpenter)

Yuki Hirano has now settled into life in Kamusari after completing his forestry apprenticeship. While he has grown more comfortable with the rhythms of rural life, Yuki remains an outsider, striving to understand the village’s deep-rooted customs and its mystical connection to the land. As he listens to the tales shared by the villagers—legends, personal histories, and anecdotes—Yuki begins to see how these stories shape Kamusari’s identity and his own sense of purpose. It’s almost as if you’re given a behind-the-scenes look at how legends and myths are formed.

Read my full review here: Kamusari Forest Series

Orbital by Samantha Harvey

It was a strange perspective to be floating in outer space with the characters. Space is often portrayed as glamorous and thrilling, but the monotony of life on repeat was a new feeling for me. It’s not something I had ever thought about.

The descriptions of no food texture, isolation, and constant physical transformation make you wonder whether you’d ever be up for space travel. As the author observes, only those who can envision limitlessness are truly suited for such a life.

The prose put me in a trance. It is almost meditative in a way, it takes you through the mundane routine, but makes you think about life and everything.

Read my full review here: Orbital Book Review

Gaban by Munshi Premchand

The story revolves around Ramanath, a young man who dreams of a life of luxury and prestige but doesn’t have the drive to achieve it. To impress his wife, Jalpa, and society, he resorts to embezzling money, leading to a series of escalating troubles.

The concept of materialism and impressing society is more relevant today than ever. As the author states, Jalpa didn’t ask for jewellery but was always happy to get them, prompting Rama to indulge her even more.

As a striking contrast, the author shows how Rama’s parents have lived an austere life since the father, Munshi Dayanath, was strict about not borrowing any money and only taking what he was paid officially. His wife, Rameshwari, didn’t have a choice but to forgo her interest in material things like jewellery.

The novel also talks about societal issues, such as police corruption, bureaucratic inefficiency, and the entrenched caste system. The melancholy of the characters seeps into the story, and by the end of it, you realise that sometimes you have to hope against hope for a better life.

Read my full review here: Munshi Premchand Book Review

The Extraordinary Life of Sam Hell by Robert Dugoni

The Extraordinary Life of Sam Hell follows Sam Hill from birth to adulthood, exploring themes of resilience, identity, faith, and the power of acceptance. Born with ocular albinism, which gives him striking red eyes, Sam becomes a target for bullying and prejudice from an early age. His mother, a fiercely devout woman, believes he’s destined for extraordinary things and pushes him to rise above the cruelty while fiercely advocating for his acceptance in a world that often judges him for his differences.

Through Sam’s perspective, we witness his struggles, his growth, and his journey toward self-acceptance. Through Ernie, the only Black student in their Catholic school, we glimpse into prevailing racial prejudice. And with Mickie and David Bateman, we see how broken homes can affect children born into them.

Sam struggles with his faith, friendships, not fitting in, and being bullied throughout his life. He feels he needs to hide his true self to be accepted. Life comes full circle at the end, and his last journey with his parents is beautifully described, capturing the bittersweet nature of love, loss, and reconciliation.

While the story has plenty of predictable tropes and ties up too neatly at the end, its heartfelt storytelling makes it a compelling read.

Adventures of Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

The book is a nostalgic and humorous portrayal of boyhood in the antebellum South. Tom Sawyer is a mischievous boy growing up in times when parental supervision was next to zero. He gets to explore, make mistakes, and learn. The novel is a series of episodic adventures, including Tom’s clever trick to avoid whitewashing a fence, his romance with Becky Thatcher, and his escapades with his friend Huckleberry Finn.

Huckleberry Finn is about him fleeing his abusive father. Huck’s journey down the Mississippi River with Jim, an escaped enslaved man, forces him to confront societal norms and his own conscience. Mark Twain critiques the racism ingrained in American culture, as Huck slowly learns to see Jim as a human being, not just someone’s property. However, the novel’s use of racial slurs and stereotypical depictions is jarring to hear/read.

You can read my review of these books here: James Book review

James by Percival Everett

The book is about a slave’s journey to finding his voice to live in freedom. The characters are mostly from Mark Twain’s book, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The story is a re-imagined version of Jim’s POV. Everett blends humour with social commentary and has moments of dark irony and satire.

In the original book, Huck learns to view Jim as human by and by. Similarly, in James, it is Huck who is questioning the world around him and learning what it’s like to be a part of Jim’s. We also meet many new characters that Jim meets along the way. Although it is not necessary to read Twain’s book to understand this, it does help with the context.

You can read my review of these books here: James Book review

Butter by Asako Yuzuki (Translated by Polly Barton)

Butter is not a murder mystery, as the descriptions suggest. Instead, it is a rich exploration of feminist themes and culinary passion. Through the story of Rika, a journalist drawn to the enigmatic gourmet Manako Kajii, Yuzuki delves into societal expectations of women, autonomy, and the power of food as both comfort and rebellion.

The prose is lush and evocative, celebrating the sensory pleasures of cooking while challenging traditional gender roles. It is a thought-provoking, unconventional read that lingers long after the last page.

You can read my full review here: Butter Book Review

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

I didn’t know what to expect from this book. It was highly recommended on social media, so I just went in blind. What a rollercoaster of emotions this book was from start to finish. We follow the Barnes family members as they go through life and learn a little about their past selves.

Dickie and his wife Imelda seem to be polar opposites and their kids Cass and PJ are trying to be their best in a dysfunctional household. As their stories unfold, the topic of climate change is also interwoven into their thoughts and actions. Dickie is building a survival bunker but will it actually save them? The ending will leave you stunned and give you some food for thought!

Name Place Animal Thing by Daribha Lyndem

Name Place Animal Thing reads like an intimate memoir but is a work of fiction, weaving together vignettes of a girl growing up in early 2000s Shillong. Through her eyes, we meet eclectic characters (locals and others who have come to call Shillong their home) linked by her perspective as she grows from a wide-eyed child to a watchful young adult.

Stories like Bahadur and Bi’s quietly expose the unspoken hierarchies of class, as the girl begins noticing how her privileged world contrasts with the lives of those who serve it. There are plenty of nostalgic snapshots of carefree childhood, but the real star is Shillong itself—its misty hills and colonial charm giving way to modernity.

It is also part of my JCB Literature Prize lists book review

West with Giraffes by Lynda Rutledge

I thought this was a book about giraffes, but they’re only in the background in a crate being transported from New York to California. So, that was a disappointment.

The story is about an orphan, Woody Nickel, trying to escape to a better life, and he convinces the caretaker of the giraffes that he is the right driver to drive the rig across the country. They come across several adventures on the way (a lot of them seem too contrived) and learn about trust and empathy.

The author interspersed the story with glimpses of Woody in an old age home writing his memoir, which I felt was completely unnecessary. The book also has snippets of news reports on the actual event of the giraffes being transported.

Zero Stars, Do Not Recommend by MJ Wassmer

The book starts off with a silly premise – the sun has melted like a yolk sliding off the egg, and now the guests at the island resort must figure out how not to descend into anarchy. Kind of a Lord of the Flies situation, but where we see class warfare instead of survival of the fittest.

Things get very interesting towards the end. The protagonists, Dan and Mara, must get through the end of times without losing their love or compassion. But Dan is a reluctant hero for the times.

It’s a good palette cleanser book with a touch of seriousness for the times and lots of silliness to get through it.

I Remember Abbu by Humayun Azad (Translated by Arunava Sinha)

A touching story about how a young girl remembers the war for Bangladesh’s independence through her father’s letters and stories. It leaves you with images of children in war zones who don’t understand why they can’t play outside, or why some people they love don’t ever return.

It is a short read but conveys the message clearly, and the illustrations are good as well.

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng

The book is a description of Penang in the 1920s when it was still a colony and expats were the dominant class in society.

We follow a British woman, born and living in Penang, Lesley, as she and her husband welcome William Somerset Maugham as a guest to their home. The story unfolds from the viewpoints of Lesley and Maugham, alternating between them. We also learn something about the history of the region and the people mentioned in the book.

Lesley’s story is that of many women who choose to stay in a marriage of convenience. Maugham’s is that of a writer travelling to get away from his wife with his gay lover, working as his assistant. We meet Dr Sun Yat Sen as he plans his revolution. We also follow the (true) story of Ethel Proudlock, who was charged with murder.

There are many lives that intersect and make this an interesting read.

The Overstory by Richard Powers

The lives of nine individuals are told by way of their connection to trees, how they’ve been affected and now must do something to save them. It is a mesmerising mix of fact and fiction. The beautiful way nature and trees are described make you want to climb on to a platform a hundred feet above on a redwood, or fiercely want to protect the utter destruction of old forests happening around the world.

It is a text-heavy book but if you have the time and imagination for it, it takes you on a journey. The structure of the book is very unique in the way it tells the story and also the way it is divided into the major parts of a tree – Roots, Trunk, Crown, and Seed.

It is meant to jolt you out of your comfort zone to recognise the irreversible tragedy of deforestation and climate change, so it is not sugar-coated in any way.

I loved the interesting facts about trees intertwined with the storyline. I didn’t understand the point of Neelay. The book can feel morbidly slow and long-winded, which dilutes the urgent call to action.

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli (Translated by Elisabeth Jaquette)

The story starts with a mundane look into the daily routine of an Israeli army commander in the desert near the Egyptian border to clear the area of any Arabs before Israeli settlers can move in. His platoon finds a young nomadic girl in the area. The soldiers repeatedly rape then kill and bury her in the sand (based on a real incident).

The second part of the book takes place decades later, when a young woman in Ramallah comes across this minor detail in the history of the region and is obsessed with finding out more information. As she goes on a short journey to the scene of the crime, we see the current situation through her eyes—the fear, the restrictions, and the occupation.

The story-telling seems mundane but the devil is in the minor details and between the lines. There’s no judgement in the words. She just narrates what is happening and that starkness hits you more than anything else.

Read my full review here: Palestinian Stories

When the Cranes Fly South by Lisa Rizdén (Translated by Alice Menzies)

Bo is an old man at the end of his life. His wife has dementia and is an an institution, he cannot manage to even to go to the toilet in time so needs to be cared for by carers who take turns visiting him, his only friend is also dependent so they talk only on the phone, his son visits once in a while but there seems to be an emotional distance.

But Bo has Sixten, his constant companion with a wagging tail. Now Hans, his son, wants to give Bo away to someone who can better care for him. The story is being told in first person as Bo talking to his wife, telling her about his childhood, their marriage, and their son. The book will make you confront your fears about your last days and who will be there by your side.

Lorenzo Searches for the Meaning of Life by Upamanyu Chatterjee

This book sneaks up on you from a slow crawl to a sprint. We start the story with a 20-year-old Lorenzo in a quaint Italian town who is unsure of what lies ahead for him. But he finds his calling in the rhythm of prayer and simplicity through a church group. The descriptions of his serene life and surroundings, combined with his devotion to his service, made me consider abandoning my modern existence to join him in that sun-dappled cloister.

When Lorenzo’s journey catapults him from his peaceful sanctuary to the vibrant chaos of Bangladesh, the book transforms along with him. He lives, learns, and meditates on what life was, is, and can be. His wish to be useful and find purpose and meaning in his life is what drives him from one project to another.

The book also highlights the difference between seeking religion for one’s own peace and seeking it to help others. It might feel like a slow read, but it is a good journey.

It is also part of my JCB Literature Prize lists book review

Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi

The journey starts with the spirits that embody a fetus and are supposed to return to their home once the baby is born. But, the gates are closed before they can return and are now part of the baby girl Ada. We follow Ada through her life but from the POVs of the different spirits that are within her.

It is a unique way to look at how a child deals with trauma and what goes on in her mind. It did get repetitive but that is also part of the journey. We see Ada fall into the same destructive behaviours as a result of her past. She can only move ahead when she learns to deal with it. The book is part biographical, part magical realism, and part grim reality, making it an interesting read.

Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt

A beautiful story of how we find connections in this world even after we think we’ve lost everything that matters. Tova is an old woman living alone in a small coastal town. She has lost her husband to cancer and they lost their son to the sea many years ago. She goes on living a routine life cleaning the aquarium at night then one day she sees the resident octopus out for a stroll. They form an unlikely bond while both decide how they want to spend the rest of their days.

Cameron, on the other hand, is a drifter. Ever since his mom left him as a child, he has never been able to keep any attachments; relationships, education, or jobs. He thinks he’s finally found a way to get a pay day and moves to Sowell Bay where he meets a myriad of characters, including Tova. Their lives converge in a heartwarming way.

It is a little slow paced but entertaining, especially the octopus’ POV. The plot twist is expected and is gently revealed. I like the light humour and small town ambience of the book.

Small Boat by Vincent Delecroix (Translated by Helen Stevenson)

I heard about this book through Dua Lipa’s podcast and was intrigued. It is a thought-provoking work from the POV of the coastguard after a dinghy carrying migrants capsizes resulting in their deaths. We hear her inner monologue as she justifies her actions of not sending the rescue boats. There is also a chapter from the POV of one of the migrants as they describe the events of the night. It is a difficult read.

There are many instances when the writer wants us to reflect on our own choices and thought processes. Do we do much other than outrage online? Are we not complicit in some ways?

I would say my only criticism of the narrative would be showing the inner turmoil of the coastguard where she struggles to deal with the guilt imposed on her. I doubt most people in position feel any guilt and have a feeling of righteousness instead.

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

This was a short and quick read but a heavy one! Bill Furlong delivers coal to a small Irish town, and the story unfolds a week before Christmas. He happens to enter the nunnery and find young girls working there and one of them pleads with him to rescue her. He slowly understands what is happening but can he go against the mighty Church? Would you rather do the hard thing or spend a lifetime regretting “the thing not done, which could have been”?

Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enriquez

This is a collection of short stories based in Argentina dealing with gruesome crimes and haunting tales. They don’t follow the standard storytelling framework of a beginning, middle, and ending so, some of them left me a little baffled at their purpose. But each story draws you in immediately into the world and doesn’t let you ignore the harsh realities even though you’d rather look away.

The stories seem normal on the surface but something darker lurks just beneath. The first story itself startled me, about a small boy raised on the streets with news of horrific murders going about. The book is classified in the horror genre and brings home the fact that the scariest of all tales is not about a made up monster, but of those living among us.

My Friends by Fredrik Backman

I was not planning to read another Backman. They’re good stories, of course, but the long drawn out style of revealing small details can try my patience. However, I needed something hopeful for the last book of the year, and it delivered.

It started off ominously, but left me feeling a tad bit optimistic for the year to come. The vivid descriptions of childhood and the strong friendships formed due to trauma bonding, all of them make you invested in each character’s path.

There are plenty of gems across the book, including some thoughts on art and relationships, and how different people see the world differently: “Grief is a luxury for those living an easier life.” “But I don’t think the most important thing for an artist is being able to draw, but having something to say.” A good read for young adults trying to find connection and meaning in their lives.

Also check out my other lists for 2025:

Note: Some links are part of an affiliate program, which means that if you click on a link and buy something, I might receive a percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you.

Leave a comment