Humans in history and humans in the cosmos. The wind and the ocean currents. The circular flow of water and air that connects the entire world. We are connected. I pray that we are connected.

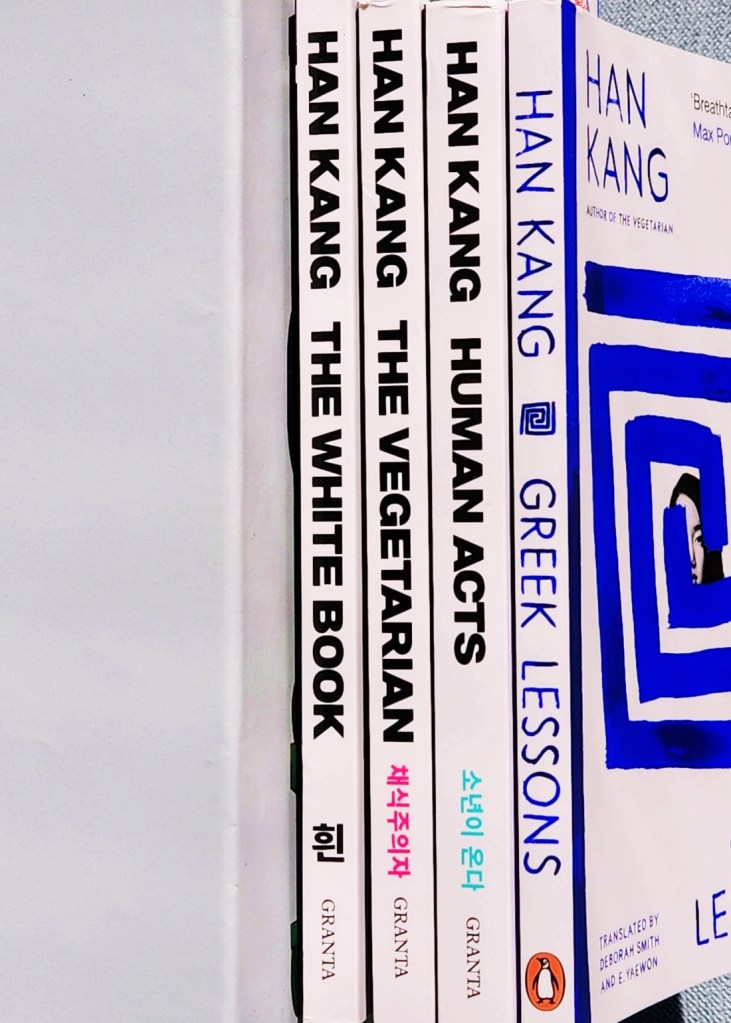

Korean literature has come to the International spotlight with some brilliant translated works. Han Kang is one such author who is one of Korean fiction’s must-reads. Han Kang’s books are not for the faint of heart—they are for when you want to confront pain, sorrow, and trauma instead of ignoring or resolving them. Her works don’t offer neat resolutions or a way out; instead, they immerse you in the complexities of trauma, loneliness, and the unspoken frustrations of being misunderstood. Her characters linger in moments of intense emotional upheaval, and as a reader, you feel everything alongside them—sometimes too much.

For an immersive experience, I decided to read four books by Han Kang back-to-back. Each novel carries an undercurrent of intense emotion, pulling you into a world where you feel too much of everything. Her exploration of trauma and its ripple effects—on individuals and those around them—is nothing short of brilliant.

Having heard about her on various forums suggesting South Korean authors to read, I was looking forward to reading her books, and they left a lasting impression. Here are my quick reflections on each of these unforgettable books.

Why is the world so violent and painful?

And yet how can the world be this beautiful?

The Author: Han Kang

Han Kang is a South Korean author. Han Kang books explore themes of pain, isolation, and the complexities of emotional and societal struggles. Born in 1970 in Gwangju, South Korea, she studied Korean literature at Yonsei University and later ventured into writing, publishing her first poetry collection in 1993 and debuting as a novelist in 1994.

Her international breakthrough came with The Vegetarian (2007), which won the 2016 Man Booker International Prize and captivated readers with its haunting portrayal of rebellion, desire, and the limits of autonomy. Her writing is often called experimental, full of metaphors, and it dives deep into themes like violence, grief, and patriarchy.

In 2024, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for her “intense poetic prose that confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of human life”, a first for an Asian woman and for a Korean. Read her acceptance speech.

Each time I work on a novel, I endure the questions, I live inside them. When I reach the end of these questions – which is not the same as when I find answers to them – is when I reach the end of the writing process. By then, I am no longer as I was when I began, and from that changed state, I start again. The next questions follow, like links in a chain, or like dominoes, overlapping and joining and continuing, and I am moved to write something new.

The Translators

Deborah Smith is a renowned British translator best known for her work translating Korean literature into English. Born in 1987, she studied English Literature at the University of Cambridge and later pursued Korean Studies at SOAS University of London. Her passion for bringing Korean literature to a global audience led her to translate several notable works, including Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, which won the 2016 Man Booker International Prize.

In 2015, she founded Tilted Axis Press, an independent publishing house dedicated to translating and promoting works from lesser-known literary traditions, particularly from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Her efforts have contributed to raising the profile of Korean literature on the international stage.

e. yaewon is a literary translator based in Seoul, South Korea, specializing in translating works between Korean and English. She has translated notable Korean authors into English, including Han Kang’s Greek Lessons. Her translations have also been featured in publications like Granta. Emily’s work is recognized for its sensitivity to the nuances of both languages, bridging cultural and linguistic gaps to bring Korean literature to a broader audience.

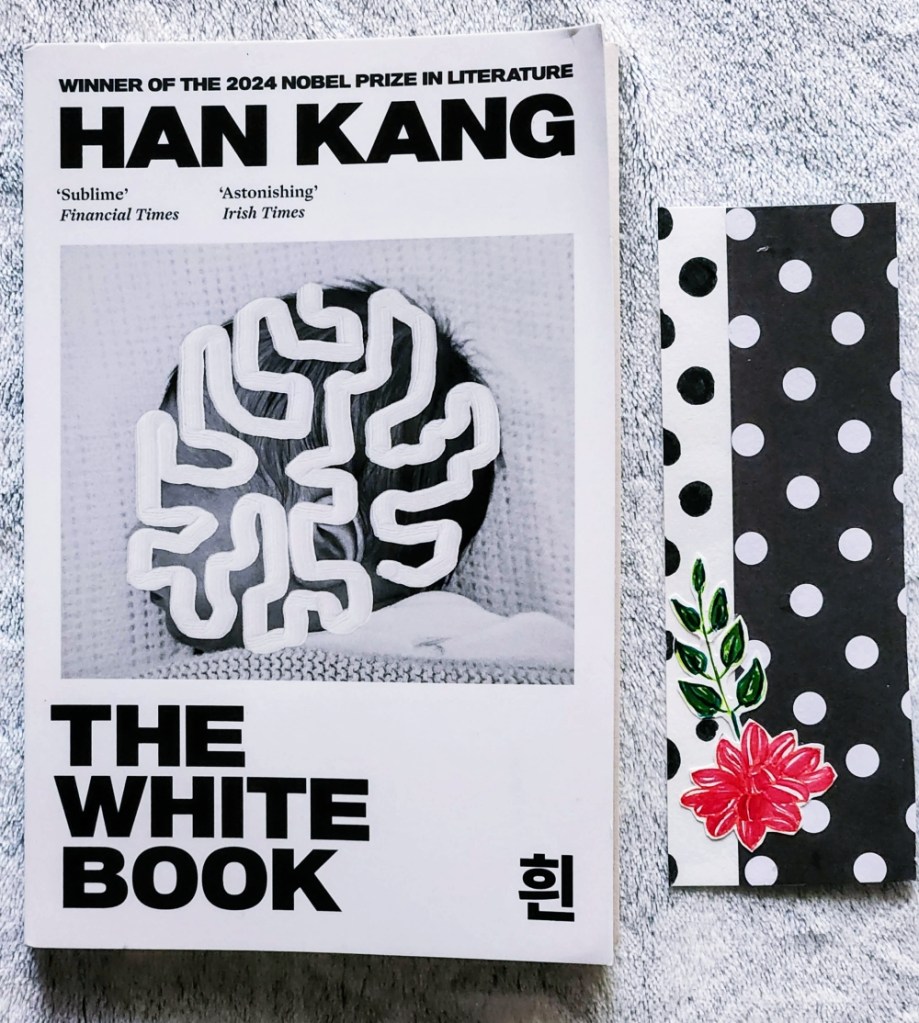

Book Review: The White Book

Looking at herself in the mirror, she never forgot that death was hovering behind that face. Faint yet tenacious, like black writing bleeding through thin paper.

This autobiographical novel is less about the story, and more about the feeling. The author talks about living with the heavy weight of loss of someone she has never even met, but grew up hearing about—her sister who died a few hours after being born.

We get to know of the story by way of the author comparing her feelings to white things, like snow or a swaddle cloth. We feel the heaviness and loneliness she lives with as she goes about her day in Warsaw.

The White Book is a collection of short paras that convey the anecdotes and musings of the author. It’s meant to be disjointed as thoughts usually flit from one to another. Apart from her personal sadness, she also reminds us of the collective grief through the city that has lived through war and trauma.

I felt the burden of sadness she carries through her words and imagery. It brought out sadness from a feeling of loss from some unconscious part of me that I never knew existed. Read with caution!

Standing at this border where land and water meet, watching the seemingly endless recurrence of the waves (though this eternity is in fact illusion: the earth will one day vanish, everything will one day vanish), the fact that our lives are no more than brief instants is felt with unequivocal clarity.

Book Review: The Vegetarian

I was convinced that there was more going on here than a simple case of vegetarianism.

Reading the reviews, I assumed The Vegetarian by Han Kang was just about society’s opposition to a person challenging the norm. But, it is so much more, where Han Kang explores repression, autonomy, and trauma.

The book has three parts, each narrated by someone close to the main character, Yeong-hye. She has a dream that makes her turn vegetarian in a culture where it’s practically unheard of. Her own POV is not mentioned, as if it is not important.

The first part is narrated by her husband. He is content with his mediocre life, which turns into an upheaval when his wife decides to turn vegetarian. He violently tries to make her see sense then eventually gives up and leaves.

Yeong-hye’s decision to give up meat—a seemingly simple choice, spirals into a disturbing journey of alienation and self-destruction. Her quiet rebellion against traditional expectations exposes the fragility of her relationships and the oppressive structures that define them. No one tries to understand the root cause of her decision, and rather focuses on ‘fixing’ her somehow.

Her elder sister, In-hye, feels obliged to care for her. Her artist husband is strongly drawn towards his sister-in-law. His desire makes for the second part of the book. His repressed emotions and struggle to find joy in his mundane life leaves him exhausted till something awakens in him when he learns of Yeong-hye’s Mongolian Spot. When he takes this relationship a step further for art’s sake, In-hye discovers the sexually-explicit video recordings and he flees in shame.

In-hye is left to pick up the pieces on her own. She takes care of her sister and young son, while managing a small business. It was heartbreaking to hear her part of the story. She says that both her sister and her husband could give up on reality and be free but she has to hold on to reality and be responsible even if she is too tired to even sleep. Her son’s efforts to make her laugh through the pain is heart wrenching.

The novel is as much about the body as it is about the mind, exploring themes of control, identity, and the boundaries between humanity and nature. The violence of life and the internal turmoil and fatigue in each person as they deal with life feels personal at times.

I think the point of the book is to make you uncomfortable about the brokenness each of us has inside us, and the pessimistic state of the world.

The novel was originally a short story called The Fruit of My Woman

The feeling that she had never really lived in this world caught her by surprise. It was a fact. She had never lived. Even as a child, as far back as she could remember, she had done nothing but endure.

She was no longer able to cope with all that her sister reminded her of. She’d been unable to forgive her for soaring alone over a boundary she herself could never bring herself to cross, unable to forgive that magnificent irresponsibility that had enabled Yeong-hye to shuck off social constraints and leave her behind, still a prisoner. And before Yeong-hye had broken those bars, she’d never even known they were there.

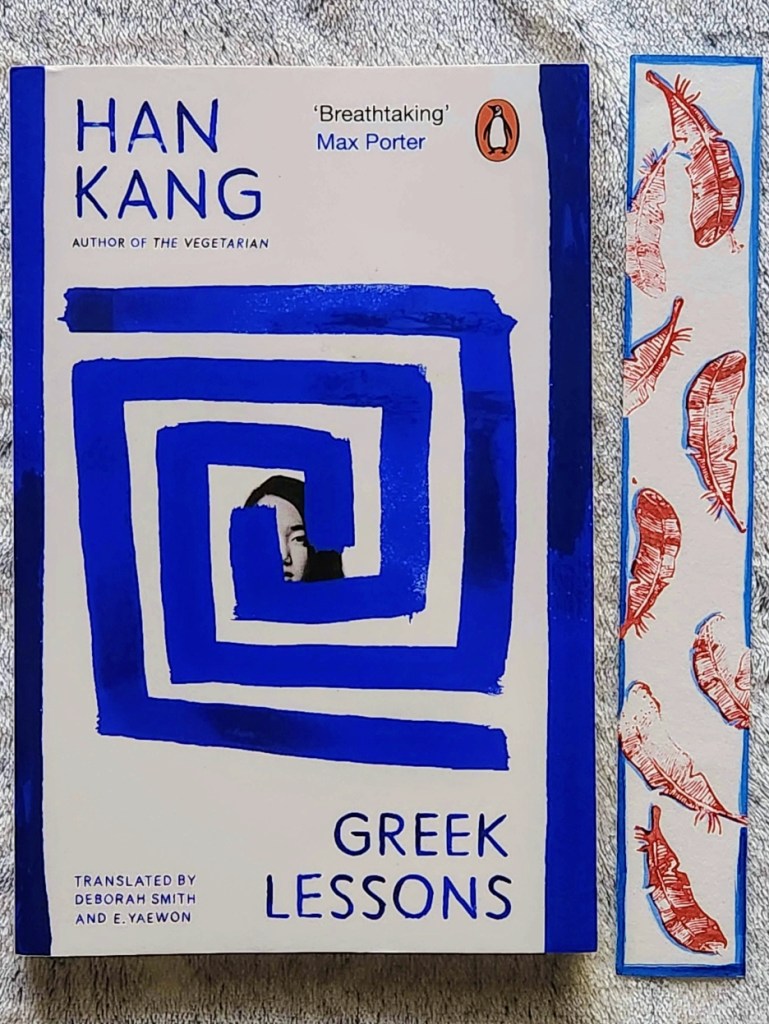

Book Review: Greek Lessons

Language, by comparison, is an infinitely more physical way to touch. It moves lungs and throat and tongue and lips, it vibrates the air as it wings its way to the listener.

In Greek Lessons, Han Kang tells a story about two people navigating loss and loneliness in their own ways, yet somehow finding a fragile connection with each other. The novel gives us two perspectives: a Greek language professor slowly losing his sight and a woman who has lost her voice, both literally and figuratively.

The professor spends his days reflecting on his past—a childhood spent in Germany, a love he couldn’t hold on to—and the uncertainty of what’s to come as his vision fades. Meanwhile, the woman is trapped in her silence, carrying the unbearable weight of losing custody of her son. I could feel her raw pain when she wanted to scream at her husband over the phone for taking her child, but no sound comes out.

Their lives intersect in a Greek class, where the professor teaches and the woman is a student. For her, learning Greek is a way to rebuild her connection with a new language without confronting her past which is sure to come up if she even thinks in her native tongue.

Han Kang’s writing makes you feel every little thing. One chapter, where the woman walks home hyper-aware of her surroundings, felt surreal to me. I could feel the texture and sensations of the world around her but it was like watching it all on mute. It’s that disorienting, dreamlike feeling of just going through the motions when everything inside you feels broken.

What’s remarkable is how Kang contrasts their stories: the professor’s voice is told in the first person, full of introspection, while the woman’s story is written in the third, emphasizing her inability to express herself. Towards the end, both these voices come together searching for the same thing—a way to feel less alone.

While the book is about pain and isolation, it’s also about the small, quiet ways we can reach out to others, even when words fail us.

If snow is the silence that falls from the sky, perhaps rain is an endless sentence.

To her, there was no touch as instantaneous and intuitive as the gaze. It was close to being the only way of touching without touch.

You said, This thing we call life mustn’t ever become something endured.

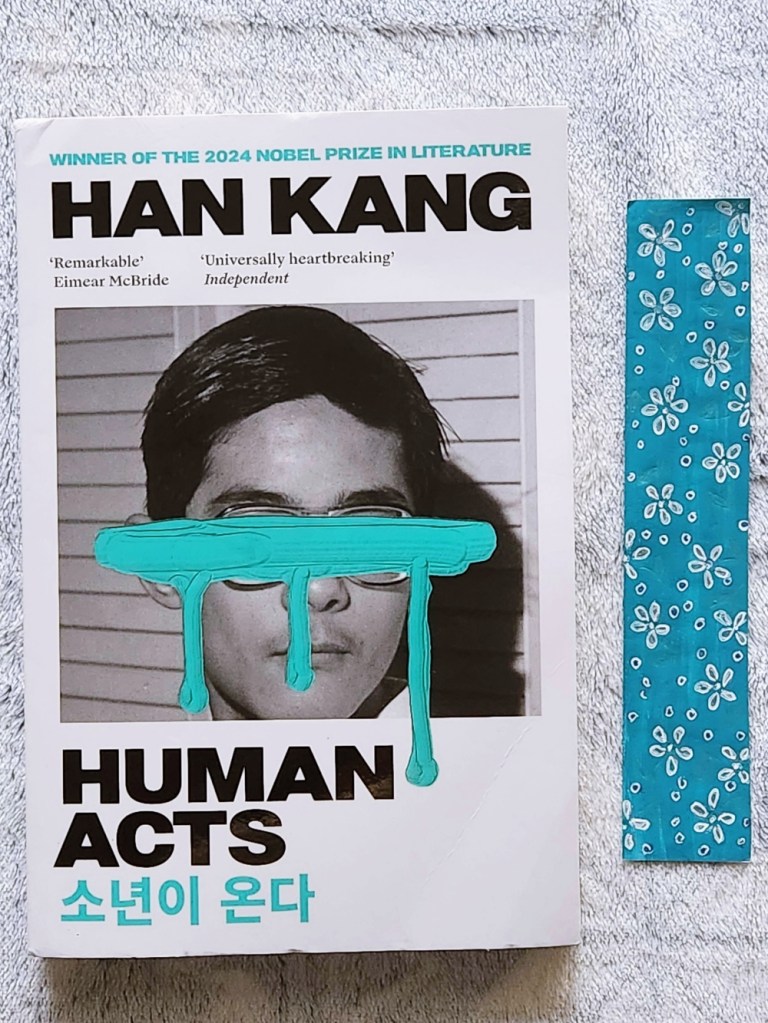

Book Review: Human Acts

After you died I could not hold a funeral, And so my life became a funeral.

There are two ways to read this book. You can feel everything, which is terrifying, or you can read it indifferently, which is also terrifying. Either way, you’ll need a moment to grieve at the end of it.

Partly based on true accounts and partly fiction, Human Acts recounts different stories of people during the 1980 Gwangju Uprising and the years that followed. Each story is told from the viewpoint of a different person at a different point in time, each grappling with grief, trauma, and the lingering scars of political oppression. The author gives you hardly any time to come to grips with the reality of State-sanctioned mass murders as young men (or their ghosts) describe the scenes of death around them. The narrative shifts perspectives across chapters, giving a panoramic view of how collective and individual suffering intertwine.

This is not an easy read but it’s a necessary one. Human Acts confronts the horrors of history while asking questions about grief, humanity, and the enduring impact of violence.

Why are we walking in the dark, let’s go over there, where the flowers are blooming.

Is it true that human beings are fundamentally cruel? Is the experience of cruelty the only thing we share as a species?

Then I read the diary entries of a young night-school educator. A shy, quiet youth, Park Yong-jun had participated in the ‘absolute community’ of self-governing citizens 6 that formed in Gwangju over the ten-day uprising in May 1980. He was shot and killed in the YWCA building near the provincial administration headquarters where he had chosen to remain, despite knowing that the soldiers would be returning in the early hours. On that last night, he had written in his diary, “Why, God, must I have a conscience that pricks and pains me so? I wish to live.”

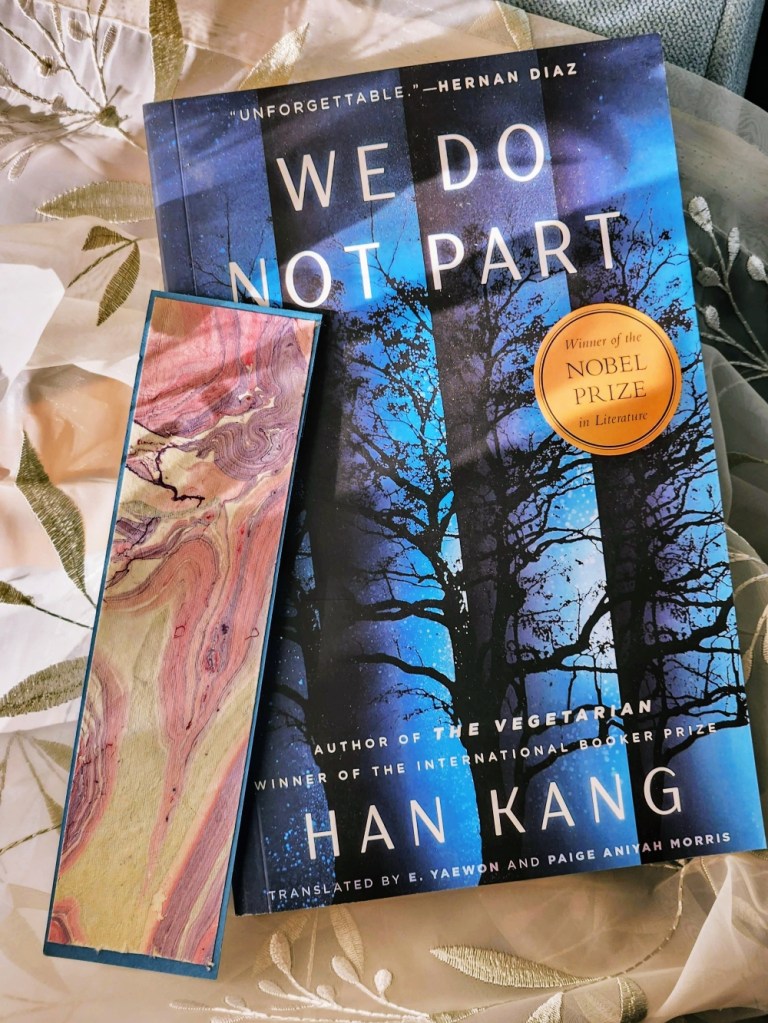

Book Review: We Do Not Part

..people walked past the window in bodies that looked fragile enough to shatter. Life was exceedingly vulnerable, I realized. The flesh, organs, bones, breaths passing before my eyes all held within them the potential to snap, to cease – so easily, and by a single decision

In We Do Not Part, Han Kang doesn’t explicitly tell you about the violence that has been committed. She eases you in with a friendship between two women, talks about despair, and then the floodgates open. Inseon has suffered a serious woodworking injury (I would give a trigger warning, but then the whole book would be redacted). She calls a trustworthy friend she hasn’t spoken to in years to go to her secluded home on Jeju Island and save her pet bird. Kyungha makes her way through a snowstorm and is reminded of all that has happened on this tiny island, not too long ago.

Almost in a dream-like state, she looks back on the Jeju Uprising and the consequent massacre that happened between 1947 to 1954. It is unfathomable the level of violence humans are capable of and equally touching is their resilience. Inseon’s mother had lived through the “troubles’ and was haunted by the memories throughout her life. Inseon carried on that legacy of trauma without fully understanding it till she was much older.

This harrowing history is told so poetically that you get caught up in the flow. Even after 50-60 years, the collective trauma lingers somewhere deep, and meaningful human connections are all that keep people living somewhat sane!

Paige Aniyah Morris is the co-translator for this book along with e.yaewon.

I had no sense of what my life had been before. I had to think really hard to remember anything at all. Each time I did, I asked myself where the current was taking me. Who I now was.

Verdict: Must Read

Note: Some links are part of an affiliate program, which means that if you click on a link and buy something, I might receive a percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

Leave a comment