For six years, the JCB Prize for Literature has been one of India’s most prestigious literary honours, recognising outstanding works of fiction and elevating voices across Indian languages. Established in 2018, the award celebrates Indian novels that combine literary excellence with bold storytelling. Its ₹25 lakh prize was one of the largest in Indian publishing. However, in 2024, the JCB Literary Foundation announced the prize’s discontinuation, marking the end of an era.

As we bid farewell to this influential award, I wanted to revisit some remarkable winners and nominees I’ve read and would recommend to anyone wanting a peek into the diversity of thought, and being in India.

Jasmine Days by Benyamin, translated by Shahnaz Habib

(2018 JCB Prize Winner)

The story is told by way of letters. Sameera, who lives in City, is writing to someone named Javed about the happenings in her life. We don’t know what their relationship is till the end.

Sameera’s life is turned around after she arrives in the City from Pakistan to stay with her father and get a job. Her job as a radio jockey is more than she could dream of. As she explores the city and makes friends, we see an undertone of dissension by a poor local population against the ruling monarchy and foreign workers.

We see the life of a woman under a patriarchal household, as Sameera has to jump through hoops to do things that interest her. We also see the lives of migrants who survive on meagre incomes, which a lot of them send to their families in their home countries.

What stands out is the cruelties of the monarchy against its citizens on the basis of religion. The horrific tales of imprisonment and its effect on families, and the burden of knowing that they will always be treated as second-class citizens. The book references the Bahraini uprising, even though not by name. It is an inspiring, frustrating, and heartbreaking tale of a revolution that is being played out IRL in so many places around the world.

Poonachi by Perumal Murugan, translated by N. Kalyan Raman

(2018 JCB Prize Shortlist)

This story will transport you to rural Tamil Nadu, where the protagonist is a spirited black goat named Poonachi. The book starts as an innocuous story about a baby goat but becomes a commentary about life, humanity, government, and how we adapt to survive.

As the story unfolds, we witness Poonachi’s journey from her humble beginnings as a vulnerable kid to her role as a cherished companion within a small rural household. Yet, amidst the simplicity of her existence, Poonachi confronts the harsh realities of life, including hunger, exploitation, and the relentless struggle for survival in an unforgiving world.

The moment that stuck with me was when the young goat cried in pain, prompting the others to pause and look on. However, when other kids also cried out, everyone had grown indifferent to the sound, so they resumed grazing. It reminded me of how we, as a society, have also become desensitised to the suffering around us.

Read full review here: Perumal Murugan

Half the Night is Gone by Amitabha Bagchi

(2018 JCB Prize Shortlist)

The book explores grief, faith, and human relationships in early 20th-century India. It follows Vishwanath, a celebrated Hindi writer who channels his sorrow after his son’s sudden death into writing a novel within a novel. His novel talks about complex relationships between fathers and sons, and his loyal servant Mange Ram.

The title is a reference to a verse where Lord Ram is waiting for Lord Hanuman to return with the ‘sanjeevani booti’ to save his younger brother’s life, lamenting that it is already past midnight and he hasn’t come yet.

The shifting narratives—between Vishwanath’s grief, his fictional tale, and the historical backdrop of pre and post Independence India—create a layered storyline. The book makes you feel the weight of the memories the characters hold in their minds and hearts.

The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay

(2019 JCB Prize Winner)

The story follows Shalini, a privileged young woman from Bangalore, whose life unravels after her mother’s death. Haunted by grief and a sense of purposelessness, she journeys to Kashmir, retracing the steps of a mysterious figure from her mother’s past. What begins as a quest for closure soon becomes a confrontation with the region’s brutal political realities, forcing Shalini to reckon with her own privilege, naivety, and complicity.

You will fall in love with the vivid descriptions of Kashmir’s breathtaking landscapes and feel the tensions simmering beneath its beauty. The novel gave me a glimmer of the militarised valleys of Kashmir, which are usually hidden from the insulated urban world.

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line by Deepa Anappara

(2020 JCB Prize Shortlist)

This story is meant to be a work of fiction. However, it draws inspiration from actual cases of missing children in India’s urban margins. It’s told from the children’s viewpoint, giving the story a unique perspective.

The story unfolds through the eyes of nine-year-old Jai, a bright, TV-crime-show-obsessed boy who lives in a sprawling basti near the Purple Line metro. When his classmate vanishes, Jai turns amateur detective, enlisting his friends Pari and Faiz to investigate—convinced that djinns, kidnappers, or some sinister force is at work.

Anappara masterfully balances childhood wonder with creeping dread, using Jai’s naive yet perceptive voice to expose systemic neglect and inequality. The basti’s vibrant chaos, sticky monsoon heat, blaring loudspeakers, and tight-knit desperation draw you into the story. The novel confronts harsh truths about caste, poverty, and institutional apathy, and the ending leaves you with an unsettled feeling.

Name Place Animal Thing by Daribha Lyndem

(2021 JCB Prize Shortlist)

Name Place Animal Thing reads like an intimate memoir but is a work of fiction, weaving together vignettes of a girl growing up in early 2000s Shillong. Through her eyes, we meet eclectic characters (locals and others who have come to call Shillong their home) linked by her perspective as she grows from a wide-eyed child to a watchful young adult.

Stories like Bahadur and Bi’s quietly expose the unspoken hierarchies of class, as the girl begins noticing how her privileged world contrasts with the lives of those who serve it.

There are plenty of nostalgic snapshots of carefree childhood, but the real star is Shillong itself—its misty hills and colonial charm giving way to modernity.

Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree, translated by Daisy Rockwell

(2022 JCB Prize Shortlist)

There are books that tell you a story, and then there are books that take you on a journey. The latter might not be for everyone. It needs to be read at the right time and frame of mind.

In Tombs of Sand, from beginning to end (and there sure are a lot of pages in between), not a lot happens in the story, but at the same time, so much is happening. It is a story about family dynamics, old age, embracing life, and so much more.

It revolves around three central characters, Ma and her two children, Bade and Beti. We understand them through each other’s eyes and thus learn more about their journeys.

Read my full review of Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree

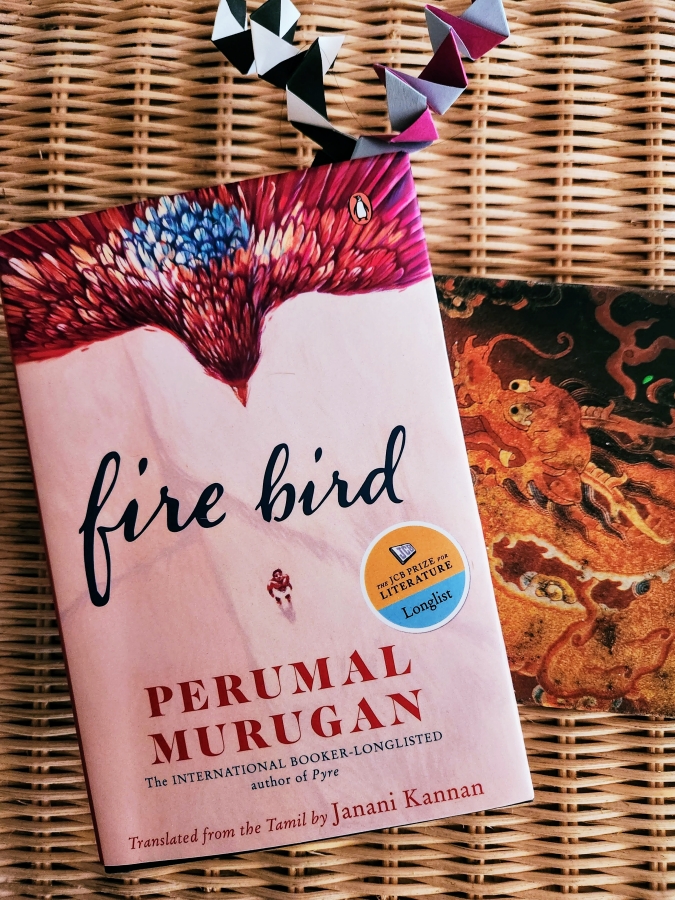

Firebird by Perumal Murugan, translated by Janani Kannan

(2023 JCB Prize Winner)

Perumal Murugan takes us on a journey of self-discovery. We follow Muthu, who is forced to leave his ancestral home in search of a new piece of land after being cheated out of his share of the family property.

Muthu’s wife, Peruma, is the youngest daughter-in-law and the target of her mother-in-law’s harsh criticisms. Upon her insistence, Muthu takes the bold step of leaving his family. His wife insists they move to a new land where no one knows them, and they can start afresh.

Set against the backdrop of rural Tamil Nadu, he talks about how relationships change over time over seemingly trivial matters. It is a simple tale told with much feeling. You want them to succeed in finding their peace and pride away from petty family politics. Although it is about a farmer, it could resonate with anyone trying to leave the old behind while forging a new path ahead.

Read full review here: Perumal Murugan

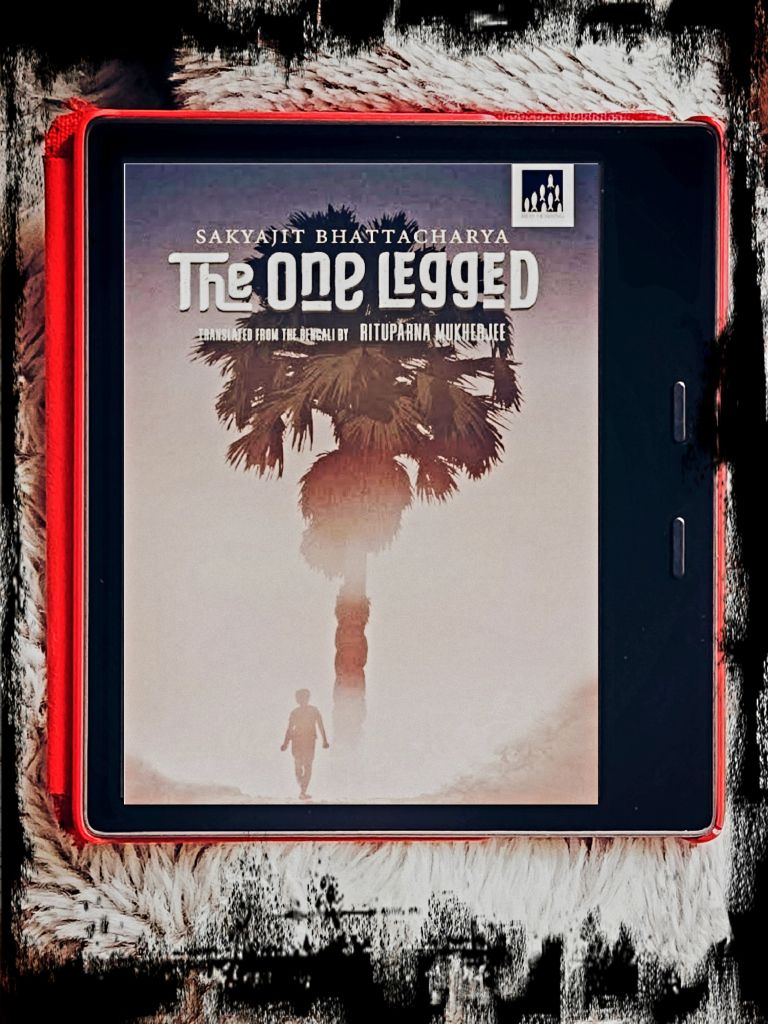

The One Legged by Sakyajit Bhattacharya, translated by Rituparna Mukherjee

(2024 JCB Prize Shortlist)

This novel’s slow, descriptive pace carefully builds suspense, and it feels like you’re watching a movie as the story unfolds. The setting, the build-up, and the climax are masterfully executed, drawing you into a world where reality and myth collide seamlessly.

The story follows nine-year-old Tunu, sent to spend his holidays in a crumbling rural Bengal mansion with his grandparents. The house, steeped in grief and haunted by memories of Tunu’s uncle, who vanished twenty years ago, becomes a character in itself. His grandmother, Dida, clings to the past, leaving offerings at the palm tree where the mythical one-legged ghost, Ekanore, is said to dwell.

The myth of Ekanore becomes even scarier when a toddler goes missing. The climax is breathtaking, revealing long-buried secrets that redefine everything you thought you understood about the story.

The story explores the psyche of a lonely young boy and delves into themes of jealousy, neglect, and the human need to belong. It also examines the shadows cast by casteism, classism, superstition, and poverty, painting a chilling picture of societal dynamics in rural India.

Lorenzo Searches for the Meaning of Life by Upamanyu Chatterjee

(2024 JCB Prize Winner)

This book sneaks up on you from a slow crawl to a sprint. We start the story with a 20-year-old Lorenzo (based partly on someone the author knew) in a quaint Italian town who is unsure of what lies ahead for him. But he finds his calling in the rhythm of prayer and simplicity through a church group. The descriptions of his serene life and surroundings, combined with his devotion to his service, made me consider abandoning my modern existence to join him in that sun-dappled cloister.

When Lorenzo’s journey catapults him from his peaceful sanctuary to the vibrant chaos of Bangladesh, the book transforms along with him. He lives, learns, and meditates on what life was, is, and can be. His wish to be useful and find purpose and meaning in his life is what drives him from one project to another.

The book also highlights the difference between seeking religion for one’s own peace and seeking it to help others. It might feel like a slow read, but it is a good journey.

Note: Some links are part of an affiliate program, which means that if you click on a link and buy something, I might receive a percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you.

Leave a comment